Accumulated Violence, or, the Wars of Exploitation: Notes Toward a Post-Western Marxism

It is the great merit of E.G. Wakefield to have discovered, not anything new about the Colonies, but to have discovered in the Colonies the truth as to the conditions of capitalist production in the mother country.1

This essay sketches an outline of what I will call here “post-Western Marxism.”2 Though very few people really use this term, I believe that many of us around the world are working on such a project in a range of different ways because getting beyond the parochialism and sexism of much Western Marxist theorizing is crucial and urgent. Marxism, as Cedric Robinson observes, remains “distracted from the cruelest and most characteristic manifestations of the world economy. This exposed the inadequacies of Marxism as an apprehension of the modern world, but equally troubling was Marxism’s neglect and miscomprehension of the nature and genesis of liberation struggles which already had occurred and surely had yet to appear among these people.”3 Consequently, Robinson offers us Black Marxism; but I want to honor and not appropriate that crucial radical tradition in this brief sketch. Like many, I also take it as self-evident that any theoretical Marxism reconstructed to be adequate for our times must also be a feminist theory. By post-Western Marxism, then, I don’t mean a Marxism only by, or about, or for the people of the global South or any other geopolitical-cultural region, nor a Marxism displaced by postcolonial theory. Rather, I mean a truly global Marxism that builds on the insights of Western Marxism, Black Marxism, Asian, African, and Latin American Marxisms, but does not habitually universalize in a gender-blind way some fragments of the historical experiences of the United States and Western Europe. It is therefore not limited by Western Marxism’s inability to think through the social, political, cultural, and ecological realities of most of the world; I mean then a Marxist theory that is not “passing for white” in the global order of knowledge power and a Marxist theory that is also a feminist theory in this specific way.

In these notes, I make three related arguments. First, I will argue that both for Marx and for us today, exploitation is best understood not only as the private appropriation of surplus value but also as subalternization. Second, I will argue that Marx’s critique of the so-called “logic” of capital is best understood through our critical understanding of the histories of colonization; that is to say, through our understanding of what Robinson calls “racial capitalism” and world-systems analysts call “historical capitalism” since the modern histories of colonization and historical or racial capitalism are essentially two sides of the same coin. Third, I will argue that since class politics is not available to us in its immediacy, all politics is identity politics, and that what is now commonly called the intersectionality of class politics and identity politics or feminist or cultural politics is better understood as their intermediation by the something I have elsewhere called “accumulated violence” — the “agency” of the histories of exploitation-subalternization in the present.4

My point of departure in this essay is the sheer heterogeneity of proletarianized people on a world scale today; something Gramsci had already began to think through with his theory of subalternity. Marx’s much derided “immiseration thesis” now seems terrifyingly prophetic. The last several decades have now seen dramatic increases in social inequality, but, more specifically, the proliferation of qualitatively different kinds of inequality; or, as it is often called, the proliferation of qualitatively different kinds of “interlocking systems of oppression” across local and global scales. In its contemporary forms, this social heterogeneity of wage dependency has provoked debates among some Western Marxist cultural theorists regarding the theoretical significance and political consequences of the neoliberal class project of rendering the postwar Fordist accord between capital and labor flexible, the normalization of structural unemployment, the informalization of ever more kinds of work, the swelling flows of migrant labor without access to citizenship rights in the Eurozone as elsewhere. In some discussions, the resulting political agents of such segmentation of the world proletariat through these different but coordinated processes are often vaguely and hastily collected through the category of the “the excluded” and opposed to a residual and privileged working class integrated with capital via the historic Fordist compromise. For Daniel Zamora, for instance, “it is a version of this perspective that — in different degrees — remains central to contemporary leftist Marxist thinkers like Antonio Negri, David Harvey, Slavoj , Nancy Fraser or Alain Badiou.”5 Zamora finds concepts such as the “multitude,” the “precariat,” even Ranciere’s “la part des sans-part,” along with the “excluded” to amount to a redefinition of the social question along neoliberal lines, stoking enmity between “two fractions of the ‘proletariat’ — between those who ‘have given up enough, lost enough, and have had enough’ and those who are in the ‘welfare republic’” and decries this entanglement of the theoretical Left with the racist, classist stereotypes of the Right.6 Yet he can do no better than to deliver us from what he considers to be such epiphenomenal “contingent differences” by returning us to the orthodoxy of “structural” theoretical axioms regarding the “fundamental contradiction of the capital-labor relation” as if history counts for nothing in the face of a canonical text.7

But the vast proliferation of qualitatively different inequalities and oppressions especially connected to the relentless process of informalization has also provoked a substantial body of specialist research in the (often Marxist oriented or inspired) social sciences that draw our attention to a wide range of further mediations of this social heterogeneity. Beyond the question of access to citizenship rights and whatever kinds of labor rights and social security entitlements that might flow from them are questions of the length of time over the year any given household has access to wage incomes, access to educational opportunities, competence in English or regionally dominant languages, environmental protections (if any), the physical and mental health statuses of its members, exposure to (para-)military and police violence, vulnerability to state procedures of criminalization, and to innumerable forms of development dispossession that all both constitute and supplement — and in this way, make up the media of — interlocking systems of sexist, racist, hetero-normative, ableist and caste oppressions.

If we are to affirm another axiom of historical materialism and begin our critical theorization, as Brecht today might, with how “shit happens” rather than with either German ideology or the science of history or both, then the fundamental contradiction between capital and labor can only mean anything, I will argue, insofar as we grasp its mediation by what I have elsewhere called subaltern multitude social contradictions.8 The theoretical and political problem posed by the proliferation of oppressions cannot be met by unmasking the alleged contingency of Weberian status identities through the alleged greater abstraction of class analysis since it is precisely the heterogeneity and status hierarchies of the subaltern classes that need theorization. Just as Brexit and Trumpism rekindled media narratives rhetorically similar to the discourse of the excluded Zamora critiques, some commentators on the Left also argued that the “whitelash” was a “symptom of a deeper illness” than racism, sexism and homophobia.9 If the current neo-fascisms and white supremacies make it urgent for us to move beyond the deadlock that pits class politics and identity politics against each other, as some of us had thought we already had, then it is not only identity politics but also class politics that needs to be retheorized. Throughout historical capitalism and today, the proletarianized are largely the colonized and imperialized (though not exclusively by European Great Powers). For this reason, our theoretical understanding of capitalism cannot be disconnected from that of colonialism (and, I will argue, vice versa).

Accumulated Violence

We find a promising starting point for post-Western Marxist theory in the growing interest in recent years in Marx’s sarcastic critique of classical political economy’s fable of primitive accumulation.10 Rather than capital springing forth from the prudence and thrift of proprietors, Marx points instead to the violence of enclosures, colonial plunder, and the trans-Atlantic slave trade as specific violent forms of class power exercised in order to create a new trans-Atlantic, and eventually, global space making the accumulation of capital possible.11 These class projects are comprised of innumerable more specific forms of power and violence ranging from war, conquest, and genocide to impressment, criminalization, encroachment, expulsion, confiscation, monetization, taxation, commodification, debt bondage, environmental destruction, disentitlement, religious conversion and so on. Each of these strategies and tactics of class power sets in place, Marx argues, the conditions of possibility of world scale capital accumulation. Insofar as these strategies and tactics are recurrent, David Harvey renames all this as “accumulation by dispossession” and argues that accumulation by dispossession intensifies as accumulation crises intensify. This reading of Marx’s critical genealogy anchors Harvey’s theory of “spatial-temporal fixes” in class politics and struggle. “Solutions” to accumulation crises are only “found” through class struggle but as Harvey demonstrates they involve the production of new spaces and temporalities of accumulation. Though Harvey’s own work often underplays it, his mentor Henri Lefebvre’s foundational contribution to Western Marxism makes it clear that the capitalist production of space is never ex-nihilo but rather unfolds “backwards,” as in Walter Benjamin’s image of the “angel of history,” from the destruction and subalternization of other modes of socio-ecological reproduction: “the Spanish-American ‘Orders for Discovery and Settlement’” — which laid the foundations of the now globalized urban grid plan, Lefebvre reminds us — “were arranged under the three heads of discovery, settlement and pacification.” “A social space of this kind” he observes “is generated out of a rationalized and theorized form serving as an instrument for the violation of an existing space.”12 Therein lies the inner connection, I argue, between colonialism and capitalism: “Geometrical urban space in Latin America,” Lefebvre continues, “was intimately bound up with the extraction of wealth in Western Europe; it is almost as though the riches produced were riddled out through the gaps in the grid, the pre-existing space was destroyed from top to bottom.”13 In its investigations of the spaces and times of exploitation and in its theorization of their articulations, post-Western Marxism does not ignore this other “materialist telos” in human history: the reproduction of capitalist wealth and capitalist social relations of production is necessarily a “Herculean” class project of world-making, as Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker describe it in their magisterial history of the making of trans-Atlantic capitalism.14 As such, the capitalist mode of socio-ecological reproduction, indeed its productivity gains through ever greater scales of social cooperation, understood as historical process (and not as a logic but rather as the witnessed ecological fate of the collective species-being of the human body) is nothing other than the repeated destruction of other modes of socio-ecological reproduction, past and future, through the scalar expansion of its world-environments. But this also means that the distinction between settler colonialism and the colonialisms of exploitation is a schematic distinction at best which obscures rather than clarifies the geography and geometry of colonial power since land-grabbing has long been connected to environment-making for commodity production.15 Indeed, modern colonialism cannot be understood historically nor resisted today without reference to the circuit of value of capital accumulation with its specifically violent spatial production. Otherwise the history of humanity is the history of settler colonialism which begins, not with the English re-conquest of Ireland, but when we descended from the trees and colonized the savannah.

I therefore want to contextualize Harvey’s arguments by considering here a few other critical engagements with this enigmatic chapter from Capital. I hope to demonstrate here that together they provide a far more compelling account of exploitation and its links to domination and dispossession, theoretically and historically, than the standard arithmetic of exploitation based on the calculation of surplus labor time beyond average socially necessary labor time that usually stands at the center of our understanding of Marx’s critique. Let me be clear, though: I am not suggesting that this received view is wrong or obsolete. Marx’s comparison of the political and reproductive affordance of the wage to the productive and political power of cooperation proprietors of capital appropriate is pertinent as ever. The wage, however, is a social, ecological and historical institution, and not just a sum of money. Even when the fetishism of the value form is understood as social domination, capitalism’s historical and contemporary colonizing imperative is given short shrift and the possibility that the subalternized counter-environments of this witnessed historical world environment-making process might hold critical lessons for the present is overlooked.16 A qualitative account of exploitation, if I may put it that way, as accumulated violence and class war would, I argue here, take us further in the direction of the more properly post-Western Marxism that we urgently need today.

Wars of Exploitation

I begin with Silvia Federici’s classic intervention, Caliban and the Witch, which connects the violence of the European enclosures and witch-hunts to that of colonial conquest, outlining their integral role in modern-colonial state formation. Federici’s work examines both how the modern nation-state colonizes women’s fertility and sexuality and, in relegating women in the global social division of labor to the sphere of social reproduction, constitutes this subaltern counter-environment as the capitalist commons. Crucial for us here is Federici’s interpretation of the European enclosures, the witch-hunts, and colonial conquest as a counter-offensive of landlords against the political struggles of cultivators seeking to dismantle feudal warlordism. The new capitalist-heteronormative-patriarchal-colonialist state with its world empires is the outcome of this class counter-offensive.17 The reconstruction of patriarchal power as a foundation of colonial-capitalist power, it is also worth noting, both historically precedes, logically underpins, and globally over-writes Foucault’s Eurocentred theory of biopower. I will return to this point later as well, suffice to say for the moment that Federici’s analyses of the persecutions and punishments of the witch hunts and its new normalcies — the crushing of female agrarian collective power and its incarceration in a nuclearized, heteronormative, private-housewife, bourgeois, panoptic sphere — leaves one astonished that the master theorist of disciplinary-capillary power could simply ignore all this.18 But there are three other aspects of Federici’s argument that I want to note here.

First of all, the segmentation of the social division of labor in terms of the unclear and indistinct opposition between the formal and informal sector is not nearly as new as Denning and Zamora assume (even though the concepts are). Rather than trying to theorize this segmentation through a comparison between Marx’s discussion of England’s surplus population of the proletariat in his day with the growth of precarity in Western Europe and the United States today, taking these postwar developments to be the key to history, a transformation of an alleged “classical model” of employment, as Zamora, Hardt and Negri, or the Endnotes collective do, things become clearer if we consider the history of the capitalist wage system itself in its actual context of a planetary scale social division of labor.19 Federici’s account of the class struggles over enclosure highlights the ways informalization was then and is now subalternization as feminization. In constituting women’s fertility and sexuality as a new commons embedded in subsistence and domestic production and enabling capital accumulation, this domain of social reproduction at the heart of capitalist accumulation enables us to understand how exploitation in the waged formal sector rests upon a foundation of patriarchal heteronormative power. As Federici and other subsistence perspective and social reproduction feminists have argued, there is no reproduction of labor power without the reproduction of the household — however various, historically and culturally, this institution has been; and it is the household, properly speaking, that comes to any labor market to sell labor power.20

Secondly, this aspect of Federici’s argument has been confirmed and elaborated in all kinds of new ways by the feminist scholarship on commodity chain mapping.21 Such research has deepened our understanding of the multitude of ways production in the formal sector depends upon and externalizes costs to the heterogenous domain of social reproduction. The frontier between the formal and informal sector is both a frontier of class struggle and its own contradiction. This is our first glimpse of what I am calling a subaltern multitude contradiction: The long histories of class struggle over the terms and conditions of wage labor is accompanied at a world scale by struggles over proletarianization and subalternization. But let me underscore two other implications of commodity chain mapping research.

We find here a paradigmatic instance of the dialectic of quantity and quality. Thus a penny saved anywhere in the global web of commodity chains trickles up to pool in some quasi-monopoly space as the capitalist form of wealth only insofar as that saving externalizes a cost somewhere else in the network of commodity chains, in the form of super-exploitation, the breaking, burning, and poisoning of bodies as the capitalist form of poverty and its violence.

Then, regarding the body and its ecology, Federici’s argument that the reproduction of labor power, understood materialistically, is the reproduction of the household has been recently recast by Jason Moore as his concept of the oikeios. For Moore, the concept of the oikeios enables us to grasp capitalism’s dependence upon an ecological surplus of what he calls “historical nature” — modes of socio-ecological reproduction that include crucially at their core the Four Cheaps of food, energy, labor power and raw materials — which constitute the condition of possibility of various regimes of accumulation. In relation to the weak law he posits regarding the tendency of the ecological surplus to fall, Moore proposes a dialectic of the appropriation and capitalization of the ecological surplus.22 Moore here deepens our understanding of Marx’s theory of crises by drawing our attention to the role of underproduction crises in Marx’s critique.

We cannot assume any “essentialist” harmony or balance to the mix of technology, energy sources and raw materials available to a historically given regime of accumulation to be indefinitely sustainable. Marx formulates the problem as one of the potential underproduction of energy and resources (circulating capital) in relation to the overproduction of technology (fixed capital). Moore therefore observes that the very success of strategies to reduce socially necessary labor time require not only ceaseless expansion of material throughput in manufacturing but also ceaseless expansion in energy and resource extraction and agriculture in such a way that “supply volumes must be relentlessly increased while supply prices must be constantly reduced.”23 To keep this expansion going, the share of capitalized work/energy rises relative to the share of unpaid work/energy in a given historical nature but now with declining labor productivity, as the Four Cheaps become costly, increasing socially necessary labor time to keep pace with the trajectory of expansion. Any search for a spatial-temporal fix for the resulting crisis brings into being a complex of historically various interlocking Herculean agencies of capital, science, and empire through which “women, nature and colonies” are actively cheapened so that a frontier of appropriation can be linked again to a frontier of capitalization.

The third reconsideration of Marx’s critique of the fable of primitive accumulation I want to take up here is Aníbal Quijano’s essay “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism and Latin America.” Quijano’s essay is a useful point of reference insofar as its restaging of Marx’s critique summarizes a wide range of research in the historical social sciences dedicated to deepening our understanding of the “path dependent” ways colonial history continues to shape the power struggles of contemporary capitalism’s crises.

Quijano argues that the world history of colonialism remains the guiding thread to the workings of power in the following ways: Firstly, the violence of racism remains a key strategy of labor control on a world scale. Drawing on Theodore Allen’s histories of racism, Quijano argues that this regime of labor control was new in so far as earlier forms of labor control were now re-organized to produced commodities for the world market, and was ultimately globally articulated as a matrix of power. Secondly, the capitalist enterprise, the nuclear family, and ultimately the neocolonial nation-state, emerge as interdependent institutions controlling labor, sexuality, and authority, eventually on a planetary scale. Thirdly, there emerged, first in the twin inventions of America and Europe, and then through the racialization of all peoples of the world, eurocentrism as a global rationality controlling intersubjectivity, identity, and communicability. For Quijano, eurocentrism then does not mean all the knowledge of Europe or the knowledges of all Europeans, but rather a “specific rationality or perspective of knowledge that was made globally hegemonic.”24

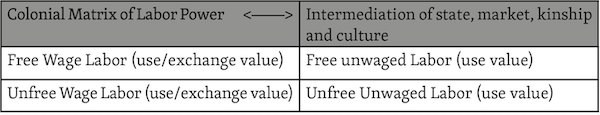

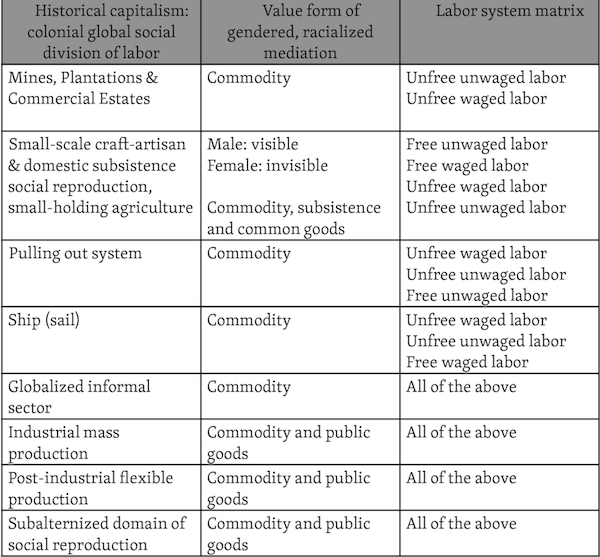

There are two key ideas I want to pull from Quijano’s coloniality of power thesis in order to amplify and elaborate the argument about exploitation I have tried to assemble thus far. The first of these is another re-statement of one of Federici’s central assertions. There has never been and there is not now “free wage labor” outside a colonial matrix of (abstract labor) power that includes free unwaged labor, unfree wage labor, and unfree unwaged labor. (See tables 1 and 2)

Historical examples of wage labor abound in the specialist literature. Reviewing the evidence from surviving papyrus documents studied by historians, Jairus Banaji points out that wage labor was well known in the ancient world where contemporaries viewed unskilled wage labor as a form of servitude. But in the historical record we also find instances of slaves not only rented out by masters but hiring themselves out for wages voluntarily. Indeed, wage labor embedded in other modes of socio-ecological reproduction where households had access to viable ecosystems and were not subject to frontier colonial violence brings a completely different kind of freedom than capitalist wage labor. This is why Marx’s own references to the concept of “free wage labor” drip with irony. For Marx has at least two lessons regarding the capitalist wage for us. The wage mediates the household’s consumer access to the fruits of world scale social cooperation and, insofar as proletarianization is a condition of separation from means of production, the capitalist wage also mediates the household’s consumer access to enclosed and urbanized nature, including, of course, technology. This double mediation amounts to an abstract and anonymous system of domination regarding which Marx writes: “In reality, the worker belongs to capital before he has sold himself to the capitalist. His economic bondage is at once mediated through and concealed by, the periodic renewal of the act by which he sells himself, his change of masters, and the oscillations in the market price of his labor.”25 But this wage-caged freedom is only possible insofar as social reproduction depends, to this day, upon a social division of labor articulating unfree and unwaged labor as well.26 Such a colonial matrix of abstract labor power, then, mediates the specificity of the concept of capital qua commodity form of value with regard to what Wallerstein calls “historical capitalism.”27

The second point I want to draw out from Quijano’s essay is its implication for the theory of intersecting oppressions and for the question of identity politics to which this theory is connected as some kind of “solution” and recuperation. The concept of intersectionality has been hailed for being “the most important theoretical contribution of women’s studies” and roundly denounced as well for being ultimately unintelligible.28 The criticisms tend to amount to the accusation that the metaphor of intersection only casts the shadow of the very reifications it opposes: analytic distinctions confused for real ones, as though there were some kind of pure racism or pure sexism prior to their intersection.29 The problem is a severe one, since the problematic of intersectionality, on the one hand, responds to the dead ends of a feminist politics hegemonized by North American white heterosexual middle class agendas facing off against an “oppression Olympics,” and, on the other, to the sheer facticity of social being wherein all identities are multiple and entangled which then threatens to bring into contradiction all political mythologies of unity and homogeneity. This is a Gordian knot that neither positivist social science, poststructuralist philosophy, nor deconstructive literary theory, despite all talk of “strategic essentialism,” can cut since the conceptual elusiveness and fragility of the metaphor of intersection is not exactly an error. Rather, the unrepresentability of an anti-essentialist intersection of essences turns on a social contradiction specific to the gap or tension between theory and praxis. For the anti-essentialists are certainly correct in their insistence that all identities are historical inventions rather than primordial essences. Yet, when Slavoj ; for example, admonishes us for moralizing politics by attempting to legitimize ourselves “as being some kind of (potential or actual) victim of power” in order to be heard, or, when Eve Mitchell denounces identity politics for focusing on our “one-sided existence and the forms of appearance of capitalism” instead of taking up “issues that put the particular and the form of appearance in conversation with the universal and the essence,” the critique may be correct, if not dead on target regarding this or that empirically specific praxis, but for that reason misses the whole point about identity.30 As it turns out with neofascism today, for instance, it is the Right that now claims to offer an economic agenda and Trumpism especially dispenses with any and all snowflake victim peddling. In this case, however, it is neither the communal essentialism nor the discursive anti-essentialism of identity nor its structural construction as ideological effect or epiphenomenon by some putatively more fundamental material base that gets to the heart of the matter. Rather, the politicization of identities seems to put at stake the very difference between a politics on the Left and that on the Right, between “social justice” and the “fascist lurking in us all”. Why and how this might be so any adequate theorization of intersections would need to clarify.

It might then seem more promising to approach the problematic of intersectionality from the direction of the “interlocking oppressions” themselves, as George Sefa Dei and Sherene Razack argue, than with regard to the identities the oppressions construct and violate. The problem then is one of locating politics in its historical situations rather than any abstract deconstruction or celebration of essentialism. Here Quijano’s survey of contemporary critical research in the historical social sciences allows us to unpack “interlocking oppressions” in terms of the historical articulations of the institutions of the household, the market, the enterprise, the state and the symbolic order by strategies and tactics of power, indeed as the violent colonization of households and kinship by the enterprise, by the market in labor power and capital, by the state and by an Eurocentric symbolic order. Moreover, the problem of the irrepressible persistence of reification dogging the metaphor of intersection can then be grasped in a new light connected to the very proliferation of contemporary inequalities and oppressions that has been our point of departure. For racism, sexism, heteronormativity, ableism, and so all down the list depend on the continual production of individuals, demographic categories of governmentality, or, from the perspective of Dorothy Smith’s Marxist-Feminism, of “abstractions of ruling relations” — economic migrants, refugees, temporary foreign workers, slum-dwellers, indigenous peoples, youth at risk, the development displaced, etc. — that can be further divided, shuffled, and recombined in all kinds of tactical ways. Moreover, as Partha Chatterjee observes, resistance to “governing most of the world” through such abstractions of ruling relations invariably involves various tactics that attempt “to give the empirical form of a population group the moral attributes of a community.”31 To operate as real abstractions, such categories, in other words, must be turned into identities, ranging from the national, ethnic, and professional to the subcultural and institution or policy specific, so the problematic of intersectional identity then returns with a vengeance.

This would then be the appropriate place to open a parenthesis on the terms power and violence that I have so far used both in coordination and sometimes interchangeably. It will be remembered that Foucault dismisses the question of violence because power does not always depend on physical violence.32 Fanon, however, insisted that colonial society is violence, and I would rather follow Fanon here, not only because of another major lacuna in Foucault’s thought.33 For it will also be remembered that in the genealogy of the discourse of race presented in the lectures published as Society Must Be Defended, Foucault examines its emergence during the English Civil War and tracks its transformation into European antisemitism and its persistence in the Soviet Union, while passing over in silence, quite amazingly, both trans-Atlantic slavery and modern colonialism. Feminist and anti-racist scholarship, however, draw attention to the link between power and violence in compelling ways, and have forged concepts of institutional and symbolic violence to do so. But, I want to insist on emphasizing the matter of violence in thinking about power for a far more important reason.

For Fanon’s enduring lesson — both anticipated and repeated ever since by the poetry, literature, and art of the oppressed — is that identities are not all historically constructed to be ontologically equivalent like signifiers qua signifier; the discursivists miss the obvious point that black identity, or indigenous identity, or immigrant identity, or feminist identity, as political identities, are not on the same plane as masculinity or with passing for white, or heterosexuality or ethnicity or national identity. On this issue, neither signifiers nor eurocentric models of power or desire are pertinent. But the specificities of colonizing capitalism, in all their diversity, are crucial. The racialized and colonized, as Fanon famously argues, are historically legislated and sentenced to a “zone of non-being” through appropriation, colonization, and racialization of the body “given back to me sprawled out, distorted, recolored.”34 In affirming this being of non-being, Fanon’s “aporetic dialectic,” as Sekyi-Otu calls it, indeed “stretches” Marxist analyses by throwing new light on Marx’s own dialectic, which seeks to render critically intelligible the fetish character of the commodity form of value. For Marx, this is ultimately a story of class violence wherein proprietors run their networks of colonizing institutions in such a way that value as the representation of capitalist wealth does not represent the common wealth on which it depends and which Herculean capitalist class power both encloses and appropriates. Marx draws on the colonial discourse of the fetish, in formation ever since the Portuguese traded down the Gold Coast of Africa in the fifteenth century, for a figure for representing the violence with which the operations of markets in labor power and capital restructure, subordinate, and in this way, colonize the ritual “markets” of reciprocal exchange that constitutes the molecular media of material life.35 In colonizing various life-worlds of political-ecological reproduction, Herculean class power, working through the institutions of “modern society” and normalizing homogeneous empty clock time, thereby transforms the content, context, and consequences of everyday reciprocal exchange, including their mediation of extant modes of domination, and so subalternizes these modern counter-environments of common being and “Hydra-headed revolt” into racialized, criminalized, misogynistically feminized non-being of “relationships between things” that thus form an abstract colonial value matrix of assets and instruments of capitalist accumulation.36

However, like Marx, Fanon’s dialectic also finds here the seeds of “sober senses” through which a counter-environmental universality that is radically different from that of the proprietors emerges as a real abstraction. So with Fanon, but also Adorno, I want to insist on the “utterly naked declivity,” the ultimate “primacy of the object,” on the historical, intersubjective, mediatory objectivity of accumulated violence through which the singular histories of subalternization interlock and with which the different oppressions are then stamped. The Eurocentric, Herculean sciences and humanities remain caught in their various racializing, exoticizing, Orientalizing idioms of repression and erasure. Nonetheless, the singular histories of subalternization are now manifestations of our common being and we can study and learn from them. But we can also now understand how and why identity politics is then the condition of possibility of class politics from below and cannot be simply explained away as the legacy of post-war social movements from the Combahee River Collective onwards plus consumerism. Rather the discourses and practices of identity of the past half-century, in whatever ways they are unprecedented, are themselves popular cultural sites of hegemonic struggle and this conjunctural experience adds weight to Etienne Balibar’s argument that there are no classes in themselves, only classes for themselves, no classes without active and organized class struggle.37 Insofar as class politics from below is by definition then a matter of mass politics, a class politics on the Left begins not merely with vague demands for jobs, better working conditions, rights in production that the parliamentary Left restricts itself to (for the Right can fight for these too), but with an organized mass struggle for the regeneration of common being and the abolition of accumulated violence as the necessary condition of a just ecology of planetary reproduction.

The last engagement with the problematic of Marx’s critique I now consider is Ranajit Guha’s theorization of Company Rule in India as “dominance without hegemony.” As Fanon insisted, one’s belonging to colonial society was fundamentally mediated by violence. Guha’s elaboration of this insight is to argue that this obtains not only with regard to the relationship between colonizer and colonized but between much else, as he puts it in his famous re-definition of subalternity, “as a name for the general attribute of subordination in South Asian society whether this is expressed in terms of class, caste, age, gender and office or in any other way.”38 The intersection of these different systems of oppression Guha then formulates as deriving “in all their diversities and permutations… from a general relation of Dominance and Subordination.”40 These two terms imply each other and this allows Guha to propose a way to historicize power “in all its aspects as an interaction of Dominance and Subordination.”41 For each of these aspects of power, Guha argues, have their correlates: “Dominance” can take the forms of “Coercion” and “Persuasion,” whereas “Subordination” can take the form of “Collaboration” and “Resistance.” As Guha explains, the “mutuality of Dominance and Subordination is logical and universal… it obtains in all kinds of unequal power relations everywhere at all times.”42 But the specific mix of coercion, persuasion, collaboration and resistance is contingently variable in different historical situations. As Guha puts it “the organic composition” of power in any particular instance “depend on the relative weights of the elements Coercion and Persuasion in Dominance and of Resistance and Collaboration in Subordination.”43

Guha’s schema for subalternist historiography allows me to specify how accumulated violence is a dimension of the social fetish as real abstraction and what this implies for a specifically post-Western Marxist theoretical practice. I have been arguing that the social contradiction between capital and labor can only be meaningful insofar as we understand it to be mediated by what I have called subaltern multitude social contradictions. I can now render this argument more sharply. In mobilizing the concept of the multitude, Hardt and Negri tell us that they mean this to be a class concept of the world proletariat, defined a concept of an “open and expansive logic of singularity-commonality.”44 While this definition then attempts to acknowledge the social heterogeneity of wage dependency that has been our concern here, the main problem this concept presents, both in Hardt and Negri’s formulation and in the way it has largely taken up by their followers, is the vanguardism of its theorization with regard to what they call “immaterial labor”: the transformation of Fordist labor processes by scientific research, communicative work, and computerization. In claiming that immaterial labor performed by the multitude is the fate of our world, Hardt and Negri claim to be following Marx’s methodology outlined in the penultimate “historical tendency” chapter of Capital.45 But Marx’s discussion there is about the crisis tendencies of capitalism, rather than some technological determinist methodology for plotting a linear trajectory of historical development. The reach of computerization throughout social life is without doubt massive, extensive and transformative, but it is neither uniform nor total. Their key thesis that the computerization of labor processes has given rise to the historical agency of the multitude embodying what Marx called the “General Intellect” does not itself account for interlocking oppressions nor contradictions through which different locations in the global social division of labor are connected. Indeed, exploitation works through the subalternizations that make up social heterogeneity. Let me offer one example from my research on the making of a software technology park in the suburbs of Kolkata, India. Both US and Indian transnational firms like IBM, Microsoft, Infosys, and Cognizant created job losses and precarity in the IT sector in North America by the outsourcing high wage immaterial work to Indian IT engineers who are cheaper only insofar as the social reproduction of such immaterial labor involves a myriad of informal sector services such female domestic service, food preparation, transportation, construction, etc. The possibility of any formal sector work connected to a relatively more robust set of political rights depends, for its conditions of possibility, upon a world scale social division of labor which is preponderantly made up of the low wage or subsistence informal sector. So the concept of multitude, in order for it to be adequate to its own definition, calls for the concept of the subaltern while the concept of the subaltern, in Guha’s re-definition, in turn calls the for concept of the multitude, if it is to now have any pertinence to contemporary South Asia or anywhere else.46 The two concepts, multitude and subaltern, then call for each other without being reducible to each other, just as singularity and the common are not reducible to each other. In my usage of the terms here and elsewhere, each concept names the way the other is not identical to itself. Moreover, we have noted that subalternity names an identity only by virtue of its counter-environmental situation by accumulated violence. In this regard, subaltern and multitude are best understood as allegorical narrative characters of such counter-environmental chronotopes that are otherwise usually marginalized or erased by Herculean accounts of history written by or for the victors. Post-Western Marxist historiography, ethnography, and cultural studies intermedia research then seeks to learn from such subaltern counter-environments. Indeed, the singular histories of subalternization and the intersectional theoretical practices of feminism, anti-racism, sexual politics, the Black radical tradition are as much necessary conditions of “revolutionary consciousness” of the “general intellect” as is science in the immaterial labor of cognitive capitalism.47 The fetish’s “magical” power is thus also contradictory: on the one hand, it structurally limits and mystifies the Herculean sciences such that the history and consequences of colonizing capitalism eludes them. On the other hand, it also makes it possible for us to render the subaltern counter-environments of common-being communicable. But the “organic composition” of accumulated violence then presents for a specifically post-Western Marxist theoretical practice what Fredric Jameson calls a “narrative form problem”: how do we represent social contradictions, especially the intermediation of subaltern multitude contradictions by the contradiction of labor power and capital, when social contradictions —which are embodied, unfold as space over time, and can be as affective as they are prosthetic — cannot be reduced to logical contradictions?48 For the question then of what the accumulated violence of our common being means to us — what singular subalternizations and suffering, what the “exhaustion of historical nature,” as Jason Moore calls it, means to us — becomes the decisive question to pose without which we cannot intervene in class politics at all. But at the same time, an interrogation of what the accumulated violence of our common being means to us also then demands some kind of utopian but practical-theoretical experimentation regarding the regeneration of common being beyond the reign of value, if theorization is to not let itself be colonized by its conditions of possibility in the accumulated violence of social practices. This question then also demands an investigation of the kinds of ecological “work,” in the non-dualist world ecological sense of this word — work qua the eco-systemic ways of our common being — that would not bring with it the fate of the planet’s and our exhaustion as historically specific capitalist labor does. Such new stories would become allegories of social contradictions. But they would also have to be stories of exploitation more specifically — at least if we are to theorize class politics dialectically, and so in terms of its non-identity with itself.

I have been arguing that the histories of colonialism are crucial to our understanding of exploitation. To this end, I have proposed the concept of accumulated violence in order to foreground the links between exploitation, domination, and dispossession, on the one hand, and as such, to argue that it is through the mediation of the accumulated violence of subalternization that the different systems of oppression interlock. I close this essay with one last observation about the way Marx tells his story of exploitation in order to bring to the foreground the centrality of colonialism to it. The ultimate force of Marx’s arithmetic of exploitation, it seems to me, is the critique of the nineteenth century’s contract ideology of the wage that he mounts through it. Not only is exchange at the labor market between wage dependents and proprietors of capital not between equals, nor freely entered into but it is not a fair exchange either. For the key question Marx poses through his arithmetical demonstration of exploitation is this: If the wage is supposed to compensate labor power for its time in production, for the opportunity cost of being commanded in this specific process of production, rather than some other, then by what rights — that is to say, by the market of capital’s own immanent rationality, by what rights? — does receipt of a wage extinguish all claims on the part of one class of production to title over surplus value as well? If the wage compensates for time, why should it compensate for the Lockean mixture as well? Why should surplus value be handed over to proprietors? At stake, of course, is the difference and contradiction between the production of capitalist wealth and the production of common wealth. Here, the deepest mystification that springs forth from the wage seems to me to derive from the temporality of the putting out system in which tools, materials, provisions, and even cash would be advanced to producers under a contract requiring pelts, slaves, fish, and now, software or even research, to be handed over to the merchant at a later time. Even at the heart of the exploitation of free wage labor, the colonial matrix of labor power remains a force of collective habit.

- Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Penguin, 1990) 543.

- This essay derives from a talk presented at the Marxist Literary Group’s Institute for Culture and Society held at Concordia University, Montreal June 25-29th, 2016. I want to thank Dr. Beverley Best for her invitation to make this presentation and the anonymous reviewers whose comments were very helpful to me in turning that talk into this essay. The missteps remain my own.

- Cedric J. Robinson, Anthropology of Marxism (London: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2001) ii.

- Sourayan Mookerjea, “Hérouxville’s Afghanistan, or, Accumulated Violence 1,” The Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 31.2-3 (2009).

- Daniel Zamora, “When Exclusion Replaces Exploitation: The Condition of the Surplus Population Under Neoliberalism,” non-site.org 10 (2016) 12.

- Zamora, “When Exclusion Replaces Exploitation” 14.

- “When Exclusion Replaces Exploitation” 18.

- See Mookerjea, “Subaltern Biopolitics in the Networks of the Commonwealth,” Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences 2.1 (2010) 245 and “Epilogue: Through the Utopian Forest of Time,” Canadian Journal of Sociology 38.2 (2013) 233-254.

- Ashok Kumar Dalia Gebrial, Adam Elliott-Cooper, and Shruti Iyer, “Marxist Interventions into Contemporary Debates,” Historical Materialism 26.2 (2018); Alana Lentin “On Class and Identity,” Inference: International Review of Science; Susan McWilliams, “This Political Theorist Predicted the Rise of Trumpism. His Name was Hunter S. Thompson,” The Nation, 15 December 2016.

- Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014); Derek Hall, “Primitive Accumulation, Accumulation by Dispossession and the Global Land Grab,” Third World Quarterly 34.9 (2013) 1582–1604; David Harvey, The New Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); Michael Perelman, The Invention of Capitalism: Classical Political Economy and the Secret History of Primitive Accumulation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000); Kalyan Sanyal, Rethinking Capitalist Development: Primitive Accumulation, Governmentality and Post-Colonial Capitalism (London: Routledge, 2007); Claudia von Werlhof, “Globalization and the Permanent Process of Primitive Accumulation: The Example of the MAI, the Multilateral Agreement on Investment,” Journal of World-Systems Research 6.3 (2015) 728-747.

- Marx, Capital.

- Harvey, The New Imperialism 151-152.

- The New Imperialism 152.

- See Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude (New York: Penguin, 2004) and Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Boston: Beacon Press, 2000).

- Patrick Wolfe, Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event (London: Cassell, 1999).

- Robert Kurz, “The Crisis of Exchange Value: Science as Productivity, Productive Labor, and Capitalist Reproduction” in Marxism and the Critique of Value (Chicago: M-C-M’, 2014); Antonio Negri, Marx beyond Marx: Lessons on the Grundrisse, (Brooklyn: Autonomedia; Pluto, 1991); Moishe Postone Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993); Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life (Cambridge: Semiotext(e), 2004).

- Sylvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation. (Brooklyn: Auotonomedia, 2004) 47.

- Federici, Caliban and the Witch 15-16.

- Caliban and the Witch 8.

- See Kate Bezanson and Meg Luxton, Social Reproduction: Feminist Political Economy Challenges Neo-Liberalism (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006); Sue Ferguson “Canadian Contributions to Social Reproduction Feminism, Race and Embodied Labor,” Race, Gender & Class 15.1-2 (2008) 42-57; Maria Mies and Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen, The Subsistence Perspective: Beyond the Globalized Economy (London: Zed Press, 2000); Joan Smith and Immanuel Wallerstein, Creating and Transforming Households (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992); Eva Swidler, “Invisible Exploitation: How Capital Extracts Value Beyond Wage Labor,” Monthly Review Archives (March 2018) 29-36.

- Wilma Dunaway, ed. Gendered Commodity Chains: Seeing Women’s Work and Households in Global Production (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013); Smith and Wallerstein, Creating and Transforming Households.

- Jason Moore, Capitalism and the Web of Life (London: Verso, 2015) 94.

- Moore, Capitalism and the Web of Life 124.

- Anibel Quijano, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism and Latin America,” Nepantla: Views from the South 1.3 (2000) 549-550.

- Marx, Capital 723-724.

- Jairus Banaji, Theory as History: Essays on Modes of Production and Exploitation (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

- Immanuel Wallerstein, Historical Capitalism: With Capitalist Civilization (London: Verso, 2011).

- Leslie McCall, “The Complexity of Intersectionality,” Signs 30 (2005) 1771-2002.

- Patricia Hill-Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (London: Routledge, 2000); J. C. Nash, “Re-thinking Intersectionality,” Feminist Review 89 (2008) 1-15; N. Yuval-Davis, “Intersectionality and Feminist Politics,” European Journal of Women’s Studies 13 (2006) 193-209.

- Eve Mitchell, “I Am a Woman and a Human: A Marxist Feminist Critique of Intersectionality Theory” Libcom.Org (2018); Slavoj , The Universal Exception (London: Continuum, 2007) 149.

- Partha Chatterjee, Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004) 94.

- Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977, ed. Colin Gordon, trans. Colin Gordon, Leo Marshall, John Mesham, Kate Soper (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972) 123.

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004)

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (New York: Grove Press, 2008) 2, 86.

- William Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, II: The Origin of the Fetish,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 13 (1987) 23.

- Linebaugh and Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra.

- Etienne Balibar, Masses, Classes, Ideas: Studies in Politics (London: Routledge, 1994) 128.

- Ranajit Guha and Gayatri Spivak, Selected Subaltern Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988) 35.

- Ranajit Guha, “Gramsci in India: Homage to a Teacher,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 16.2 (2011) 292.

- Guha, “Gramsci in India” 292.

- “Gramsci in India” 292.

- “Gramsci in India” 292.

- Hardt and Negri, Multitude 225.

- Hardt and Negri, Multitude 141.

- See Mookerjea, “Subaltern Biopolitics in the Networks of the Commonwealth” and “Epilogue: Through the Utopian Forest of Time.”

- See Virno, A Grammar for the Multitude.

- Jameson, The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992) 33.