Marxism and Form Now

This introductory essay intends to advance the core arguments of a lengthy interrogation of Marxism and form in the twenty-first century. This shorter version of the project cannot include the set of close readings and detailed examinations of individual forms and texts that conclude the longer version. What I will attempt in what follows is to foreground the basic principles of a Marxist formalist method for the contemporary conjuncture, as well as address the stakes of such a critical project in the context of contemporary discussions surrounding form, genre, literariness, disciplinarity, and reading. Such an analysis of contemporary Marxist formalism must, of course, address the currently vibrant field of new formalism, which, as I shall argue, stands at times in polar opposition to Marxist praxis. This essay therefore has two projects. As indicated by the title of this special issue of Mediations, the core of Marxist literary critique is built upon a constant process of negation and sublation, on the need to develop a Marxist critical “now” by constantly revisiting and continually questioning its own method. In this essay I will 1.) illustrate the dialectical connection between literary form and the form of thought that determines how we talk about literature (and form) in the first place, and 2.) gesture into the direction of a Marxist critical method for the twenty-first century that eclipses much contemporary controversy surrounding concepts such as reading, method, literariness, literature, literary history, and form by developing a negative dialectical account of form in historically specific relation to a general process I will describe as capitalism’s cultural regulation.

The Way We Talk About Form Now, or “I Placed a Form in Tennessee…”

There is much now-ness in contemporary critical discourse. Over the course of the last few years, literary critics have occupied themselves with questions such as: What is literature now? How do we argue now? What is form now? What is genre now? How do we teach now?1

Clearly present in this anxious contemporaneity in current critical discourse is a historically and materially specific crisis of futurity that is tied to a distinct sense of urgency on the level of disciplinarity. Rather than actually examining how form, genre, literature, and interpretation function in the now, however, critical output frequently remains preoccupied with discussions of why such analysis is (supposedly no longer) done, who or what has to be blamed for this trend, what the negative consequences for our discipline are, and which lost critical and literary virtues we should return to. As a result, necessary questions regarding contemporary form are replaced with a series of anxiety-laden provocations that provide us more with a series of mournful appeals to return to a lost “back then” than with critical interrogations of our “now.” The true question that underlies numerous versions of this debate is one that criticizes (rather than critiques) the present and nostalgically looks backward, instead of productively forward, a question unable to overcome the stasis of a now that is criticized for a lack of precisely the same critical sublation that we can find in its critics: “what now?” Elsewhere, I show that a similar crisis of futurity in contemporary literary production is a characteristic feature of what I call the periodic shift from postmodernism to post-Fordist culture, that is, the shift from emergent to full post-Fordism.2 What I would like to foreground in what follows is the suggestion that the strange temporality underlying much contemporary critical discourse (on the level of both its assumed urgency and its logical constitution) signals a crisis on the level of thought that is dialectically connected to a logically congruent crisis on the level of literary form.

Let me unfold the steps that will build toward this argument by turning first toward the crisis of futurity on the level of thought. Not surprisingly, we do not encounter many dialectical conceptions of the now in the midst of the present onslaught of contemporaneity. The title of this essay and of this subsection fulfills, as is doubtlessly clear by now, a double function, gesturing into the direction of both a current trend in critical production and the material and historical determinations that inform the use of the concept “now” that remain all too often unexamined. Yet, my use of “now” is not simply facetious. Rather, it constitutes a call for negative dialectical critiques of the concept of now-ness as employed in critical discourse, which allows us to launch an inquiry into the materially and historically specific structures that inform today’s approaches to questions of interpretation and disciplinarity in general and of form in particular. The most recent representative example can be found in the discussions that made up the 2008 Modern Language Association Presidential Forum (“The Way We Teach Now”), published in Profession 2009. In particular, the contributions that deal with the question of “reading(s)” are notable for our purposes. Mark Edmundson’s “Against Readings” is arranged to present a counterpoint to David Steiner’s essay “Reading,” yet the only true opposition between the pieces is contained in the essays’ titles. Both pieces are indicative of current critiques of the “now” and lament the lack of disciplinary skills and the growing inability to recognize literature’s individual status. While Steiner quotes Gerald Graff to mount a critique of contemporary literary critical flatness that allegedly merely asks students to “take sides in debates between formalist and new-historicist interpreters,” Edmundson speaks out against “readings” that simply throw random theoretical models (the differences between which are negligible, according to Edmundson) at literary texts in order to categorize and “judge” their quality in reference to an external set of theoretical categories that do not really have anything to do with individual works of literature.3 Edmundson’s solution to the problem of the now is to stop producing Derridean, Foucauldean, or Marxist readings of Blake and instead teach Blakean readings of Blake, an argument for the resurrection of literature’s lost status of independence and autonomy, a praxis of diversity-politics criticism that tolerantly aims to “befriend the text.”4 Steiner, in turn, argues for a practice of reading that ultimately ends up foregrounding the experience of reading a piece of literature and a practice of teaching that enables students to “move beyond resistance to understanding and from understanding to pleasure and even love.”5

What is interesting for the problem at hand, however, are not the surface arguments. After all, neither characterization of contemporary critical praxis and its problems delivers a convincing or sufficiently complicated account of the most pressing crises our discipline faces. Yes, throwing theory at a literary text to see what sticks and reducing the literary text to the level of an example than can prove or extend an external theoretical notion is not what literary criticism should do. Yet, despite the fact that we all know that such “readings” are executed on a daily basis, this reductive use of both theory and literature is so fundamentally flawed and simplistically uncritical that it can be dismissed without warranting much further discussion. Of true interest here is the logical basis upon which both Steiner’s and Edmundson’s essays’ surface arguments rest. Both essays construct their project similarly. That is, both essays describe a literary-critical now that is characterized by the supposed loss of those traditional values and methods that end up robbing it of its own disciplinary identity (and we can easily see how the reduction of structural discussions regarding critical methodology and praxis to the level of identity must inevitably produce troubling logical positions). The solution to the problems of the present that are, in characteristic fashion, described as either brought about by the struggle between formalism, deconstruction, and new historicism on one hand and the influence of interdisciplinarity and cultural studies on the other (Gerald Graff’s contribution to the forum addresses this second facet in more detail), is a return to past practices and values. Ultimately, thus, both essays end up in the same logical terrain that stresses in Schillerian fashion the experiential, formative, and educative value of literature itself (of course, this assertion of the autonomy of the work of literature is in itself a theoretical position with a long tradition and its own praxis of reading). The way to fix the problems of the present, it seems, is to move ahead into the past.6

My argument here is, of course, not that looking to past practices is not a worthwhile endeavor. My argument is not that the past has nothing to offer us. Rather, my argument is that current critical praxis tends to antidialectically reach back into the past, attempting to resurrect critical methods and concepts for the now in ways that divorce thought from history. Moreover, we will see that this tendency to divorce thought from history for the sake of resurrecting lost critical projects must itself be historicized, since it is indicative of a form of thought that is gestated under specific material and historical conditions. To illustrate this point, let us turn toward the current debate surrounding new formalism. The key text in this discussion is doubtless Marjorie Levinson’s essay “What Is New Formalism?,” which is remarkable for its clear and extensive mapping of the debate’s main positions.7 While, as Levinson suggests, critics such as Ellen Rooney warn that an overly nostalgic “longing for the lost unities of bygone forms” may end up undermining the “reanimation of form in the age of interdisciplinarity,” there remain two main positions of new formalism, both attached to the past. On one side, Levinson writes, we have a strain of new formalism dominated by those who “want to restore to today’s reductive reinscription of historical reading its original focus on form (traced by these critics to sources foundational for materialist critique — e.g., Hegel, Marx, Freud, Adorno, Althusser, Jameson).” On the other side, we find “those who campaign to bring back a sharp demarcation between history and art, discourse and literature, with form (regarded as the condition of aesthetic experience as traced to Kant…) the prerogative of art.” “In short,” Levinson concludes, “we have a new formalism that makes a continuum with new historicism and a backlash formalism.”8 Once again, what is interesting here is not necessarily what we say about form now, but how we talk about it now. That is, the significant determination is that between form of thought and our discussions about form. Instead of maintaining the distinction between “activist formalism” and “normative formalism” that Levinson and a number of other critics adopt as labels for the two main strains of new formalism, it is important to note that both strains stand in troubled relationship to the past and therefore to the now.9

What, from a Marxist perspective, might at first sight appear to be a refreshing willingness to take seriously the true contributions of the Marxist tradition to literary study (without falsely and in ideologically suspect fashion characterizing it as a vulgar form of simple, inflexible materialist and political determinisms, as critics such as Edmundson still do) reveals itself upon closer inspection as an antidialectical form of thought that runs counter to the logical core of the Marxist method.10 As a result of the much-professed need to return to Adorno and Lukács and resurrect a Marxist account of form, the logic of activist formalism is indeed logically congruent with normative formalism’s intended resurrection of Kant and Schiller. The frequently encountered idealization of Marxist formalism rests on a logical paradox and assumes a situation of historical discontinuity that only makes sense if constructed from an utterly un-Marxist position that at its core precludes recourse to the logical form that constitutes the very basis of Marxist praxis: the dialectic. It is surprising, yet, as we shall see, historically coherent that even those new formalist arguments that advocate the return to dialectical critique display fundamentally antidialectical logic. It is, however, not surprising that the result should cause Levinson to characterize new formalism fundamentally as a “movement rather than a theory or method.”11 Levinson herself anticipates this argument when she writes:

Because new formalism’s argument is with prestige and praxis, not grounding principles, one finds in the literature … no efforts to retheorize art, culture, knowledge, value, or even — and this is a surprise — form. That form is either “the” or “a” source of pleasure, ethical education, and critical power is a view shared by all the new formalism essays. Further, all agree that something has gone missing and that the something in question is best conceived as attention to form …. But despite the proliferation in these essays of synonyms for form … none of these essays puts redefinition front and center.12

Consequently, Levinson argues, the work of the movement consists principally in “rededication,” that is, in the attempt to “reinstate the problematic of form so as to recover values forgotten, rejected, or vulgarized.”13 Taking Levinson’s argument to its logical conclusion, we must note that the recovery project aimed at returning Marxist attention to form to the center of our discipline runs counter to Marxist logic. The logical error in such projects, the same error that relegates new formalism to perpetual status as a movement and precludes its development into a method, is the assumption that there is such as thing as Marxist formalism.

To be sure, it is also not true to say that there is no Marxist formalism. The logically coherent formulation characteristically thinks both positions in one thought (a thought that gives rise to a series of negative positions, as well as that temporality we can understand as the history of Marxist formalist thought). The initial mistake is a traditional one, namely the false assumption of the identity of thing and concept. Yes, there is Marxist formalism, yet it has no positive value and it is precisely this positivistic assumption of a transhistoric stability residing in the idea of Marxist formalism or the concept of form itself that reveals itself to produce the antidialectical logic, which (re)produces the stasis that in part constitutes the strange now-ness we examined above. To clarify this, let us turn toward Adorno’s famous reformulation of the Hegelian dialectic that strips it of the positivistic remainders contained in the standard account of a dialectical synthesis. In his Lectures on Negative Dialectics,Adorno extends Hegel’s assertion of the need to conceive of the whole of thought as both result and process, that is, of the necessity to foreground progress and action without which the aim remains a “lifeless universal.”14 A proper dialectical method, according to Adorno, is based on a dialectic of “nonidentity,” on,

a philosophical project that does not presuppose the identity of being and thought …. Instead, it will attempt to articulate the very opposite, namely the divergence of concept and thing, subject and object, and their unreconciled state.15

Thinking takes place via concepts. Form is one such concept. One way to interrogate such a concept would be to compare and contrast it to other concepts — content, for example. Yet, concepts make claims toward unity. That is, each concept contains a variety of elements, and in order to arrive at conceptual unity, we take from each of these elements those parts they all have in common. Those common parts then become the concept. Yet, Adorno stresses, we also “necessarily include countless characteristics that are not integrated into the individual elements contained in this concept.”16 It is for this reason, that Adorno famously stresses that concepts are always at the same time smaller and larger than the characteristics that are subsumed under it. And it is for this reason that we must at every moment not simply study the contradiction between different concepts (say, the contradictions between the use of the concept of form in activist formalism as opposed to its use in normative formalism), but we must also study the contradictions within the concept itself. If, therefore, we speak of the concept of “Marxist formalism,” we must do so bearing in mind the negative dialectical account of concepts. The concept of “Marxist formalism,” just as the concept of form itself in proper Marxist analysis, has no positive and certainly no transhistorical content. Rather, form in Marxism is in its totality an infinite series of negative relations without positive terms (that is, without positivistic synthesis). Nostalgically idealizing Adorno’s or Lukács’s notions of form and formalist methodology empties these concepts of the dynamic core the methodology rests upon and, by ignoring one of Marxism’s central lessons — the study of an object’s immanent contradictions — resurrects Marxist formalism as an antidialectical, a priori concept. And it is on this level that we find another explanation for the tendency of seemingly opposed levels of argumentation (in our case, reading and not reading, activist and normative formalism) that ultimately find themselves in the same logical universe: Kantianism. One result of the lack of negative dialectical, immanent critiques of the concept of form itself is new formalism’s characteristic production of an unhistorical, oppressive now-ness.17

In the context of this messianism of form(alism) that, as with all forms of messianism, must remain a temporally troubled and antidialectical movement hoping for the spontaneous emergence of (disciplinary) reform out of the empty shell of a method, the way we talk about form becomes of vital importance and reveals its dialectical connection to the things we say about form. Fredric Jameson famously gestures into the direction of the connection between analyses of form and form of thought in the classic Marxism and Form. Dialectical thought in Hegel, Jameson writes, “turns out to be nothing more or less than the elaboration of dialectical sentences.”18 Such dialectical sentences are missing from the dominant current discussions about form, and it is this lack we sense in the undialectical awkwardness of the use of the concept of “now” in current sentences and titles.19 It is once again not simply the movement or project that matters, but, in the face of a missing dialectical method, the call for a return to Marxist formalism disappears into its own temporal and logical incoherence. After all, as Jameson suggests, “any concrete description of a literary or philosophical phenomenon — if it is to be really complete — has an ultimate obligation to come to terms with the shape of the individual sentences themselves, to give an account of their origin and formation.”20 This line of reasoning is extended in Jameson’s interpretation of Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness as a key text for literary critique. While seemingly mainly concerned with political and philosophical problems, Jameson argues, Lukács works through epistemological problems that take on a central role in discussions surrounding literary form. History and Class Consciousness indicates that critiquing literary form is always dialectically connected to a process of critiquing both the concept of form and forms of thought. It is Jameson’s linking of Marxist formalist critique and Lukács’s critique of a form of thought connected to the famous Kantian “thing-in-itself” that becomes of vital importance to our current project of examining contemporary forms of thinking about form.

Jameson shows that Lukács’s critique of Kantian descriptions of the relationship between subject and external reality, out of which emerges the famous notion of the noumenal, assumes that the notion of the “thing-in-itself” constitutes an optical illusion that arises from a particular form of thought. This optical illusion emerges as a result of a “prephilosophical attitude toward the world which is ultimately socioeconomic in character: namely, from the tendency of the middle classes to understand our relationship to external objects … in static and contemplative fashion.”21 In other words, the inability to conceive of external objects as anything but static noumena is dialectically connected to a historically and materially specific form of thought that remains unable to grow “aware of capitalism as a historical phenomenon.”22 The Kantian problem of the thing-in-itself therefore presents itself as a socioeconomically specific one in which a purely contemplative form of thought is produced out of, and, in turn, produces, middle-class social experience and understanding of the capitalist structure. The trademark of such a purely contemplative attitude is the elimination of history from concepts, that is, the idealization of either timeless or transhistorical concepts, which, in the absence of change, are turned into noumena. Lukács’s famous critique of Kantian thought that short-circuits the dialectical connection between form of thought and historically and materially specific structural forms is to insist upon a definition of Marxist praxis that conceives of objects in terms of change. It is here that (despite the great number of differences) we find a logical link between Adorno’s negative dialectical notion of concepts and Lukács’s understanding of objects, reality and totality as process and progress. Both positions stress the centrality of contradiction and negation without relying upon positive terms.

If this is so, and if the critical discussions we concern ourselves with here are similarly characterized by contemplation, stasis, and the reduction of method to movements (tellingly movements without progress), what is it that determines the form of thought that characterizes current discussions? What explains the static and purely contemplative nature of new formalism, especially on the level of its arguments about form, and what are the structural forms whose reified manifestations we find in current forms of thought about form? Especially in the context of new formalist debates we get a glimpse of a specific contemporary segment of theliberal tradition of thought, which shines through in arguments that advocate the return to the mythical time in which literary scholars still talked about form and provided a stable basis for a disciplinary identity. Such arguments remind us of Jameson’s famous critique of liberalism as bankrupt yet pervasive, and of its focus on the individual case, rather than on a complex network of relations.23 It is impossible to develop here an adequately complex description of the current socioeconomic juncture as employed in my general analytic framework. I begin to sketch out such a description in a previous issue of Mediations.24

For the moment, let us simply focus on one aspect of the current historical moment, which I develop from the basis of French regulation theory that provides us with a valuable economic model which helps us extend the dialectical connection between structural form and form of thought with which we are concerned here, namely its study of capitalist history as a result of its social regulation. The Regulation School establishes a dialectical connection of capitalist structure (Regime of Accumulation) and its social dimension (Mode of Regulation) and foregrounds moments of crisis as the motor of capitalist development that produces productive disturbances on both levels of the equation: Regime of Accumulation (ROA) and Mode of Regulation (MOR). Doubtless, the most prominent crisis today is the crisis of neoliberal capitalism, whose end is already being celebrated by a great number of scholars and commentators.25 The structural crisis’s effect on the social dimension is on the level of thought with which we are all familiar, that is, a form of thought that, on the level of philosophy, effectively and once and for all buries the postmodern project. The free-market project has failed, many argue, and after a period of free-market anarchy, chaos, and the tearing down of the safe regulatory structures of Fordism that gave way to post-Fordism’s chaotic system, it is finally time to return to (frequently Rooseveltesque) traditions of capitalist regulation. It is not hard to spot the logical congruency between those advocating the return to capitalist regulation in times of free-market chaos and those calling for the return to traditional, stable disciplinary structures in an age of interdisciplinarity-induced instability.

On the level of cultural production, we frequently encounter descriptions of the present moment that are characterized by what William Gibson in his 2007 novel Spook Country calls “the terror of contemporaneity.”26 What was once perceived as the liberating free-market narrative of post-Fordist structures whose rise was supported and made possible by the philosophico-cultural project called postmodernism, is now often represented as a form of oppression resulting from the standardization of difference and diversity. (Especially in the case of the latter concept, whose signification and socioeconomic function have changed radically over the course of the last few decades, we can once again see that it operates in materially and historically specific fashion.) Cultural production experiences a much-publicized crisis of futurity that is most clearly visible on the level of utopian form. Jameson already anticipates this trend in his 1996 The Seeds of Time, an argument publicized by Slavoj Žižek in the documentary Žižek!. Both argue that we have seemingly lost the ability to represent small changes in the socioeconomic structure; yet, we have no problem imagining scenarios of complete global devastation. What they consider a crisis of imagination reveals itself here as the reified form of a troubled relationship to the structure of contemporary capitalism, which in its insistence on deregulation and productive chaos complicates the project of identifying dialectical contradictions that can guarantee future progress. A notable example is the proliferation of postapocalyptic narratives as critiques of the present socioeconomic situation whose inability to recover futurity via dialectical sublations of the “now” always seems to require a system-reboot via narratives of destruction that allow for the recovery of traditional values and forms of subjectivity. In a recent commentary on the contemporary economic situation, Robert Kurz describes the idealized return to governmental regulation of economic structures as a “backwards flip” that tends to treat neoliberalism as a mistake, which can be fixed via the return to Keynesian values. Yet, Kurz stresses, what we are looking at today is neoliberal Keynesianism and, as such, not the same as Keynesianism “back then.”27 What we are looking at, thus, is not a return, but instead a different stage of neoliberalism. Yet, just as in the discussions that dominate our discipline, the central characteristic of an argument in favor of neoliberal Keynesianism is the inability to come to terms with the changing nature of the concept of Keynesianism itself, hence, similarly dooming itself to a frequently static existence in an awkward “now” that cannot find a way to produce the new.28

I also suggested above that, in addition to linking form of thought and structural form, we can dialectically link form of thought and literary form. Lukács’s great contribution to literary study in History and Class Consciousness,according to Jameson, is that he resolves the problems of nineteenth-century philosophical thought not on the level of philosophy. Rather, Jameson argues, “the ultimate resolution of the Kantian dilemma is to be found not in the nineteenth-century philosophical systems themselves, not even in that of Hegel, but rather in the nineteenth-century novel.”29 It is not in scientific knowledge, Jameson argues, that Lukács finds his answer to the problem of the noumenal, but in literary plot and in the novel’s formal arrangements that include the formal composition of characters. It is precisely such an analysis that once again resolves the impasses on the level of scientific thought in general and of new formalism in particular.

The Seeds of the Real: Cultural Regulation, Form, and Literary History

As in the case of the critique of new formalism and contemporary critical now-ness, I can here provide only a few brief examples that indicate the direction the full analysis of literary form and Marxist formalism take, as presented in the longer version of this essay. What, then, are those developments on the level of literary form that can allow us to work out some of the problems on the level of philosophical and disciplinary thought? The last twenty years or so were an eventful time for American literature. Postmodernism and its trademark formal experimentation effectively exhausted itself at the moment at which its sociopolitical, philosophical, and cultural core revealed itself as a short period in sociopolitical and philosophico-cultural history whose productive output significantly contributed to resolving the structural crisis of Fordism and facilitated the transition into a new mode of development: post-Fordism. It is at this point — Fordism’s structural supersession and the transition into full post-Fordism, at which postmodernism and its cultural forms develop their full functionality in regulation of the post-Fordist structure — that we begin to witness a large-scale crisis of literary representation that registers especially significantly on the level of form. Contemporary U.S. literary production is characterized by what is frequently described as the renaissance of older forms. Most notably, as a number of critics have argued, we have witnessed a widespread return to realism, American naturalism, and the historical novel. The examples of this return to realism are countless and include works by authors such as Annie Proulx, Richard Russo, Jonathan Franzen, Chang-Rae Lee, Cormac McCarthy, Geraldine Brooks, and Bret Easton Ellis, as well as the recent novels of William Gibson, Kim Stanley Robinson, Thomas Pynchon, and Don DeLillo. To be sure, this formal shift is not specific to literature and can also be observed in other media, such as film, TV, photography, and installation art. Does this development, then, constitute a “return” to forms such as realism and an attempt to turn back the clock to the times before the emergence of postmodernism’s formal experimentation that evolved parallel to post-Fordism as a result of the structural crisis of Fordism beginning in the 1960s?30

Of course, we know by now that the answer to this question must be a resounding “no.” Instead, we have to understand this development on the level of culture as logically congruent with the regressive ideology of neoliberal Keynesianism. In A Singular Modernity, Jameson likens postmodernism to a failed revolutionary project, undermined by nostalgia, fear of true revolutionary innovation, and the persistent, bourgeois attachment to tradition. What he calls “the return of the language of an older modernity” is for Jameson, hence, a distinct sign of the postmodern and of its inherently bourgeois character.31 I would argue, however, that we can more accurately understand postmodernism as a successful, and not as a failed, revolution, and that the return of the “languages of an older modernity” that Jameson associates with postmodernism is, in fact, indicative of postmodernism’s exhaustion in particular and the completed sociocultural and economic shift into full post-Fordism in general. The return of past forms that we currently witness, in other words, does not constitute a failure of a revolution of the kind described by Marx. To be sure, it is easy to put together a long list of contemporary works of literature that wholeheartedly embrace the nostalgic idealization of a mythical lost time that provided stability and protection (and that was characterized by a literature that formerly corresponded to such values), thus paralleling the antidialectical nostalgia of those mourning the loss of old economic structures, social values, and disciplinary identities. Yet, such works that coherently reproduce on the level of form the regressive and statically ahistorical attitude of new formalism are not very interesting to study. Yes, there is coherence we could point toward in order to further the line of argumentation introduced above. Much more interesting, however, would be to ask the Lukácsian question: are there works of literature that formally resolve the crisis of futurity we witness in so much mainstream cultural production and thought?

In the longer version of this essay, I illustrate why the answer to the above question must be an excited “yes” by turning in part toward the work of William Gibson. Yet, Gibson’s work, arguably among the last few decades’ most valuable objects of study for analyses of the dialectical connection of literary form, form of philosophical thought, and capitalist structure, has been receiving a considerable amount of critical attention. Instead of discussing Gibson’s latest novels, therefore, I will here take the opportunity to foreground the importance of the work of Kim Stanley Robinson, which is of similarly high value for the discussion at hand. Robinson is most well known for his complex interrogations of the concept of Utopia, usually via the vehicle of hard science fiction. The Mars Trilogy and The Three Californias (sometimes also referred to as The Wild Shore Trilogy) are usually considered the key works in his oeuvre. Critics have not devoted much attention to his most recent trilogy, the Science in the Capital trilogy, in part, because it does not quite seem to fit with Robinson’s previous work. Instead of grappling with speculative fiction and narratives set in the future, Robinson has recently turned his attention to realism and narratives of global politics in the present. Hence, one could seemingly argue that Robinson has abandoned his traditional concerns and has fallen prey to the contemporary crisis of futurity that makes the production of utopian representations of a future that has not yet come to pass impossible. A more precise way of reading the formal shift of Robinson’s fiction, however, arrives at the opposite conclusion. Switching to realist form is a continuation of Robinson’s ongoing exploration of the dialectical relation between form and socioeconomic history by means of radical shifts in formal register. As do other authors such as Gibson, Octavia Butler, Cormac McCarthy, and Colson Whitehead, Robinson presents us with a novelistic form that addresses the currently pervasive crisis of futurity in an attempt to wrest a utopian impulse from the grip of the current structural and epistemological impasse.

In order to illustrate this point, let us briefly look at the characters that dominate Robinson’s latest novels. If we study characters in contemporary novels, we can relatively easily complete a process of simple pattern recognition and arrive at a series of characters that remain coherent within the structural logic of post-Fordist capitalism. In a previous issue of Mediations, I illustrated that the figure of the absent or troubled father is one such character that mediates the struggle between anti-paternalistic structure and its social dimension in post-Fordism.32 Yet, such an analysis only tells part of the story. That is, it only reveals those narratives that are congruent with the crisis we are examining here. What is missing from such an analysis is the examination of those kinds of works of literature that dialectically resolve the crisis. For Lukács, the difference between Zola’s and Balzac’s ability to resolve the problem of epistemological stasis through realist form registers in part on the level of characters. The key difference in this distinction for Lukács lies in the notion of “typicality,” which, as Jameson stresses in his analysis of Lukács’s argument, allows him to distinguish between characters that indicate a form of thought directed at historicity and historical change, as opposed to a static form of thought that reduces characters to types and, as such, to “mere illustration[s] of a thesis.”33 In other words, Lukács faults Zola for constructing characters that in their typicality resemble archetypes of the now, while Balzac’s characters are “not typical of a certain kind of fixed social element, such as class, but rather of the historical moment itself,” thus generating an appreciation of historical change through contradictions (as opposed to perpetuating the stasis of the now by means of its typicalization).34 In our case, it is easy to find contemporary versions of Zola — authors who may well understand some of the pressures of the now, yet who remain unable to transcend the process of representation as typicalization, consequently freezing history instead of dialectically driving it forward.35

The great value of Robinson’s novels is that they resist precisely such typicalization and instead thematize it in order to supersede the crisis that produces the general tendency toward typicalization in contemporary cultural production. Rather than telling the story of the now through characters that represent Robinson’s preexisting thesis regarding the present, he provides us with a matrix of conflicting positions. Science in the Capital may be frustrating for the reader who expects to find a Marxist character who provides smart answers to present problems. Yet, this was never a characteristic of Robinson’s fiction and of his affinity with dialectical thought. If such a character existed in his novels, Robinson would not just be guilty of the same typicalization as Zola, but also of the same antidialectical logic we find in new formalist attempts to resurrect Marxism. More rewardingly, Robinson provides us with a wide selection of characters: many display various shades of (neo)liberal thought, luddites, empiricist positivists, Buddhist monks, (fiscal) conservatives, and libertarians. What his novels leave us with are sets of negative relations, networks of contradictions that set up the most significant political and philosophical tensions that determine our present. These negative networks, in turn, resist static, purely contemplative typicalization and instead set up a dialectical relationship between characters and the now. We find the same formal strategy on the level of plot, where dialectical contradictions drive forward a process that never suffices itself with positivistic (or satisfying) resolutions: libertarians struggle with neoliberals who struggle with neoconservatives, Buddhists struggle with humanist leftists, philosophers struggle with scientists, capitalism struggles with sustainable development, and luddite politics compete with the ideal of terraforming. Plot and character development are driven by contradictions, that is, by constant change arising from the network of negative political and philosophical positions without clear positive terms resisting the static typology we find, for example, in the work of Jonathan Safran Foer and Dave Eggers and which corresponds to the antidialectical conception of form in new formalism. Instead of providing us with a host of characters that represent the predetermined positions authors such as Bret Easton Ellis mobilize for the purpose of social critique, positions that are inevitably reduced to petrified fragments of a world frozen in time, Robinson’s characters remain at every point connected to an unresolved, dialectical multipositionality. Far from abandoning it, Robinson reconstructs Utopia as the dialectical process it is and mobilizes it in historically specific form in ways that allow us not just to thematize but to begin to work through the epistemological pressures of the now. Reading Science in the Capital means to dissolve what we conceive of as paralyzing impasses (politically as well as formally) and show them, as Lukács would have it, as the multipositional processes they are.

This line of argumentation is, of course, connected to a fundamental concept that informs the Marxist critical method: the problem of mediation. In the context of his analysis of Sartre, Jameson channels his account of the concept through the following set of questions: “How do we pass … from one level of social life to another, from the psychological to the social, indeed, from the social to the economic? What is the relation of ideology, not to mention the work of art itself, to the more fundamental social and historical reality of groups in conflict, and how must the latter be understood if we are able to see cultural objects as social acts, at once disguised and transparent?”36 This set of questions is of vital importance to current discussions about (Marxist) formalism. That the political is firmly located in the cultural is a common suggestion by now. Yet, this is only a part of the whole problem, and even as such, is never explored to the full level of consequence it indicates. Following the logical determinations of the arguments above, it becomes clear that we have arrived at a definition of culture that locates it at the heart of the dialectical interconnected of material structure and the sociopolitical force field that is as much produced by this structure as it, in turn, produces, or, more accurately, regulates, this structure itself. Put in terms of the Regulation School, culture is located in the center of the dialectical struggle between Regime of Accumulation and Mode of Regulation and can be represented in the following manner:

ROA <--> Culture <--> MOR

I would here disagree with Jameson’s suggestion that culture can serve as an “introduction to the real,” less complex than the economic, which it “reduce[s]” and “simplifie[s].”37 In our current juncture, culture must rather be seen as the area in which both the economic and the social are gestated in dialectical fashion. Culture, in this sense, is the battleground in which structure and social dimension meet in dialectical struggle. Hence, culture is neither mirror nor hammer, but the very thing that allows the dialectical struggle between structure and social dimension to take on concrete forms. Culture is the fertile ground which sprouts the seeds of the real that grow into the perpetual process of the dialectical struggle between structure and society. The economic writings of the Regulation School hence provide us with a productive basis for tying together the separate levels of argumentation above and illustrate the degree to which capitalist structure historically progresses as a result of crises, that is, as a result of the dialectical struggle with its social dimension. This formulation illustrates the dialectical connection of structural form and form of thought, the tension between which presents itself to us as one of the motors of history. Furthermore, we have seen that crises are carried out on the level of culture that includes the dialectically connected levels of literature and theory (theory is thus far from exterior to literature — instead, it is part of the large realm we call culture).

This all leads us to a final conclusion, which is that, especially in times of full post-Fordism (of which cognitive capitalism, immaterial production, consumer capitalism, and Media Society are individual facets rather than alternative concepts), the Regulation School’s notion of the social regulation of capitalism has to be extended. Full post-Fordism is characterized by capitalism’s cultural regulation.The concept of cultural regulation must be understood in the context of the logic that stresses the nonidentity of thing and concept, of subject and object. Furthermore, the concept of cultural regulation includes a negative dialectical understanding of form that stands in immediate relation to history, that is, as filled with historically specific and perpetually moving, yet structurally specific, contradictions. Consequently, the problem of form is best examined in relation to a process of cultural regulation; in the case of the argument at hand, this is exemplified by the social, structural, and cultural “standardization of difference” that has become a trademark of post-Fordism.

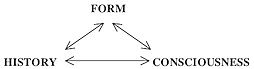

My Japanese teacher used to tell me that, when trying to pronounce an “r” syllable, I should utter a mixture between “r” and “l” and think of a “d” (unfortunately, one of the few lessons I still remember). This is exactly the way in which we need to think literary history: we always, at the same time, need to say “history” and “consciousness” while thinking “form.” Marxist accounts of form are also accounts of literary history, and the Marxist method is based on a dialectical triad that periodizes by linking history-form-consciousness in a mutually informative manner:

This formulation links critical and literary form, theory and cultural object, history and criticism, and assigns formal change a vital function in the supersession of moments of structural crisis. Literary history, by extension, is the history of the cultural regulation of capitalism that progresses through crises and registers on the level of form. Form is the manifestation of the cultural regulation of capitalism that is itself a network of negative relations. All that is not capital can on this account be understood as culture. In full post-Fordism,culture has no other besides capital. We are, therefore, not confronted with the subsumption of culture under capital in the context of full postmodernity. Rather, we witness the full development of the dialectical relation between capital and its social dimension as a battle carried out on the field of culture. Full postmodernity or post-Fordism is the full transition into the cultural regulation of capitalism. It is in this situation that a rigorous focus on negative dialectics in analyses of form is endowed with particular urgency.

In addition to the texts discussed below, see Amanda Anderson The Way We Argue Now: A Study in the Cultures of Theory (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2005), whose title I rhetorically invoke, volumes 37 and 38 of New Literary History (2007), which are dedicated to the problem of “literature now,” volume 61 of Modern Language Quarterly (2000), which is dedicated to the problem of form today, and Mark David Rasmussen’s collection Renaissance Literature and Its Formal Engagements (New York: Palgrave, 2002) that likewise contains a number of essays concerned with the question of form now.

See Mathias Nilges, “‘We Need the Stars’: Change, Community, and the Absent Father in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents,” Callaloo 32.4 (2009): 1332-52.

See Mathias Nilges, “‘We Need the Stars’: Change, Community, and the Absent Father in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents,” Callaloo 32.4 (2009): 1332-52.

David Steiner, “Reading,” in Profession 2009, ed. Rosemary G. Feal (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2009) 53, and Mark Edmundson, “Against Readings,” in Profession 2009, ed. Rosemary G. Feal (New York: Modern Language Association of America) 61.

Edmundson, “Against Readings” 64.

Steiner, “Reading” 55. Of course, this position is not new. Yet, what is interesting about such critiques of and fixes for contemporary literary studies is both their proliferation at this particular moment in history and their diachronic and synchronic location in critical discourse. A more detailed analysis would, therefore, map this line of argumentation in diachronic location to affective categories that formed one of the bases of the beginnings of the postmodern turn (see, for example, Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation) and in synchronic relation to the current proliferation of another affective turn. Such a project of mapping would, at least in part, study those structural and epistemological forms that dialectically determine the turn toward affective criticism that reconstructs literature as an ahistorical entity (and arrive at not very surprising results, as this essay indicates). Yet, I should also mention one further position here, and I am indebted to Emilio Sauri for referring me to the essay that exemplifies this position. Lindsay Waters’s “The Rise of Market Criticism in the U.S.” (Context 20) constitutes an impressive and very interesting misreading of Walter Benn Michaels’s recent scholarship. To be sure, Michaels’s work neither requires nor invites (and maybe does not even deserve) defenses. The productive dimension of Waters’s essay for our purposes is his misreading of Michaels’s, at this point, well-known attempt to illustrate a distinct historical shift that assigns arguments that in the 1960s and 1970s may have served a radical agenda, an instrumental role in the context of neoliberalism. To Waters, Michaels’s suggestion that yesterday’s radicals are today’s neoliberals is an instance of either (or possibly both) empty logic or a populist right-wing agenda (and, at times, it also seems to be a sign of Michaels being simply mean and a bad, bad person, which ironically anticipates the argument for affective criticism that is to follow). Again, it is not my intent to defend Michaels’s argument. It is also impossible to elaborate upon the precise logical downfalls of Waters’s essay at this point. I would, however, like to suggest that Waters’s lack of recourse to dialectical thought is a sign of the current confusion surrounding both politics and the principles of literary study that, in his case, does not allow him to develop a clear analysis of the structural determinations that assign political as well as critical concepts a precise historical and material function — a shortcoming that is directly linked to the troubled conceptions of literary form I discuss in this essay. The result of this lack of dialectical critique of the historical function of concepts ends up conflating the positions of Waters, Steiner, and Edmundson (who want, yet cannot occupy, very different logical and political positions) and transforms Waters’s misreading into an example of Michaels’s point, who in turn himself remains unable to theorize the fact that we have already spun the wheel of material history past the position he examines in his own version of undialectical materialism. What we are left with is scholarship whose seemingly argumentative heterogeneity is transformed into the homogeneity of materially productive ideological positions to which I will below refer as “neoliberal Keynesianism,” a context in which necessary political and material critique is emptied out in the optical illusion of the same catch-22 Waters thinks to be able to trace in Michaels’s arguments. Michaels himself would likely and correctly suggest that he is well aware of the undialectical nature of his thought. Yet, as I suggested above, such a choice comes with a set of distinct consequences, in part endowed with a particular sense of urgency by the various levels of crisis we associate with the now of contemporary literary and cultural critique. Working through the logical and historical (and material/functional) determinations of these consequences is not simply a question of theoretical gusto, as the example of new formalism I discuss here indicates. All I can suggest at this point, is that undialectical accounts of concepts such as form, formalism, medium, and literariness are as much a threat to contemporary literary critique as they are characteristic of it, perpetuating the very crises they intend to solve. Especially since Michaels’s critique of a set of logical positions and its structural and functional evolution is supposed to contain a historical and material level of critique as well as the formulation of a transition that is contingent upon a historical change, the decision to opt out of dialectical critique produces in part the same problems we locate in the historical and logical contradictions of new formalism and other current disciplinary debates. This, in turn, causes critics to misjudge the effects of logical arguments that, in spite of their very project, become complicit with the positions they intend to undermine and reify the moments of stasis and exhaustion they lament.

Steiner’s version of an urgent appeal to restore the good old days of literary study is introduced (with much unapologetic pathos that, of course, compliments the unapologetic embrace of a time in which pathos signaled a desirable aspect of literary study) as follows: “The Emersonian fusion of classical humanist hopes for the redemptive power of literature … with American pragmatism offers not only a recovery from the arid wilderness of poststructuralist, postmodernist, postcolonialist, counterhegemonic discourses but also a path back to the glory days of F. R. Leavis and I. A. Richards, when the undergraduate study of English literature was second to none in the pantheon of the academic disciplines. Few undergraduates indeed can be expected to master a chapter of Rodolphe Gasché’s painstaking exegesis on the Derridean arche-trace — yet many would surely resonate to the invitation to heal themselves through the transformational magic of literature” (51). Edmundson, in turn, as illustrated above, intends to rescue the independent standing of literary texts, which is threatened by theoretical exegesis. For Edmundson, the current praxis of reading a literary text (which he associates with reading a text theoretically, a process that flattens the distinction between theoretical positions that are called upon to enact readings), “means to submit one text to the terms of another; to allow one text to interrogate another — then often to try, sentence, and summarily execute it” (61).

See Marjorie Levinson’s “What Is New Formalism?” PMLA 122.2 (2007): 558-69. The longer version of this essay deals in detail with a larger range of essays, in particular, those contained in the “form” issue of Modern Language Quarterly 61 (2000), Cary Wolfe’s essay “The Idea of Observation at Key West, or, Systems Theory, Poetry, and Form Beyond Formalism” in New Literary History 39 (2008): 259-76, and Terry Eagleton’s essay “Jameson and Form” in New Left Review 59 (2009): 123-37.

Levinson 559.

Susan J. Wolfson first develops the “normative/activist” distinction in her essay “Reading for Form” Modern Language Quarterly 61 (2000): 1-16.

As we will see, Edmundson’s flawed characterization of what he would consider a Marxist reading is indicative of his missing the dialectical core of Marxist critique that does not lend itself to constructing the text-theory or thought-object distinction Edmundson’s argument rests upon. What could be considered a properly Marxist “reading” is an interesting question that I shall explore elsewhere in greater detail. Let it suffice to suggest here that it is inextricably linked to the negative dialectical account of form and the link between form and text that I will explore below.

Levinson, “New Formalism” 560.

Levinson, “New Formalism” 561 (emphasis original).

Levinson, “New Formalism” 561.

Theodor W. Adorno, Lectures on Negative Dialectics, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: Polity, 2008) 5 and note 8, p. 212.

Adorno, Negative Dialectics 6.

Adorno, Negative Dialectics, 7.

This now-ness can be understood as the result of the return to a static, purely contemplative notion of the relationship between subject and object that Lukács associates with Kantianism. Contemporary returns to such formulations of art resurrect inevitably the same set of problems and the ahistoricity that Lukács associates with bourgeois liberal thought reaching back to traditional Kantianism.

Fredric Jameson, Marxism and Form: Twentieth-Century Dialectical Theories of Literature (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1971) 12. We should also note that this formulation is also key in a description of Marxist “readings,” since it stresses the dialectical connection of reading for form and form of thought.

A fitting example for this point can be found in Bertolt Brecht’s poetic version of dialectical critique that Jameson celebrates in his recent Valences of the Dialectic (London: Verso, 2009). The first stanza of Brecht’s “Hollywood-Elegien” presents us, according to Jameson, with such a dialectical sentence, prompting one of the few passages in Valences that Jameson concludes with an exclamation point: “A true dialectic; a true unity of opposites!” The stanza Jameson quotes reads as follows:

The village of Hollywood was planned according to the

notion

People in these parts have of heaven. In these parts

They have come to the conclusion that God

Requiring a heaven and a hell, didn’t need to

Plan two establishments but

Just one: heaven. It

Serves the unprosperous, unsuccessful

As hell. (410)The important point here is, of course, not solely the dialectical contradiction contained in the section’s content. More important is the dialectical connection between content and form of thought, which ultimately determines Jameson’s analysis of the passage via dialectical sentences that formally mediate the passage’s content. In other words, we see an example of Hegel’s classic illustration of the dialectical connection between form of thought and aesthetic form. In order to illustrate this point further, it is worth quoting a representative passage from G. W. F. Hegel’s Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics (New York and London: Penguin, 2004), in which he establishes the basic principles of the methods of aesthetic science, at some length The following passage illustrates the dialectical connection of content and form, as well as of the dialectical idea and the form of Hegel’s writing, which structurally reproduces the dialectical movement carried out on the level of thought. In order to arrive at the final assertion of a dialectical scientific method, Hegel takes Plato’s insistence upon the necessity to perceive objects not in their particularity but in their universality as a point of departure:

Now, if the beautiful is in fact to be known according to its essence and conception, this is only possible by help of the thinking idea, by means of which the logico-metaphysical nature of the Idea as such, as also that of the particular Idea of the beautiful enters into the thinking consciousness. But the study of the beautiful in its separate nature and in its own idea may itself turn into an abstract Metaphysic, and even though Plato is accepted in such an inquiry as foundation and as guide, still the Platonic abstraction must not satisfy us, even for the logical idea of beauty. We must understand this idea more profoundly and more in the concrete, for the emptiness of content which characterizes the Platonic idea is no longer satisfactory to the fuller philosophical wants of the mind today. …The philosophic conception of the beautiful, to indicate its true nature at least by anticipation, must contain, reconciled within it, the two extremes which have been mentioned, by combining metaphysical universality with the determinateness of real particularity. Only thus is it apprehended in its truth, in its real and explicit nature. It is then fertile out of its own resources, in contrast to the barrenness of one-sided reflection. For it has in accordance with its own conception to develop into a totality of attributes, while the conception itself as well as its detailed exposition contains the necessity of its particulars, as also of their progress and transition one into another. (25-26)

Notable here for our purposes is the dialectical connection between form of thought and sentence form. Hegel’s unfolding of the logical steps that arrive at the ultimate insight into the dialectical connection between universal and particular is itself mediated in the dialectic between content and form and ultimately between form of thought as expressed in the content of the passage and the form of Hegel’s sentences. It is here that we see the importance of Jameson’s suggestion: the dialectical form of Hegel’s thought necessitates the construction of dialectical sentences and dialectical paragraphs, that is, paragraphs that are driven by positing and sublating contradictions in order to arrive at a logical and syntactical conclusion. To be sure, it is this important lesson from which we must methodologically extrapolate when addressing the problem of form today, since it reminds us that arguments about form can be separated neither from the very form in which they are put forth, nor from the form of the progress of ideas and concepts they presuppose.

Jameson, Marxism and Form 12.

Jameson, Marxism and Form 185.

Jameson, Marxism and Form 185.

Jameson, Marxism and Form x.

See Mathias Nilges, “The Anti-Anti-Oedipus: Representing Post-Fordist Subjectivity,” Mediations 23.2 (2008).

Neoliberalism, especially on the account of regulation theory, can itself be understood as a crisis. However, in the context of contemporary capitalism, the concept of crisis itself takes on a specific function. A satisfactorily complicated discussion of this argument can thus not be carried out here.

William Gibson, Spook Country (New York: Putnam, 2007) 29.

Robert Kurz, “Neoliberaler Keynesianismus,” Exit Online at <http://exit-online.org/textanz1.php?tabelle=autoren&index=20&posnr=416&backtext1=text1.php>.> (translations mine).

Telling in this context is therefore Andrew Hoberek’s contribution to Profession 2009, in which he characterizes Stanley Fish’s approach to teaching as “Taylorized.” See Andrew Hoberek, “‘We Reach the Same End by Discrepant Means’: On Fish and Humanist Method,” Profession 2009, ed. Rosemary G. Feal (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2009) 79.

Jameson, Marxism and Form 189-90.

To be sure, formal experimentation is also a distinct characteristic of modernism. Yet, in contradistinction to modernism, postmodernism’s formal experimentation is dialectically connected to the crisis of Fordism and the beginning of the deregulation of socioeconomic structures. That is, in the context of post-Fordism’s emergent stage, formal experimentation takes on a decidedly different (cultural, structural, and epistemological) function than it does in modernism.

Fredric Jameson, A Singular Modernity: Essay on the Ontology of the Present (London: Verso, 2002)7.

See my “The Anti-Anti-Oedipus.”

Jameson, Marxism and Form 195.

Jameson, Marxism and Form 195. Of course, as Jameson suggest in this extended passage, the notion of typicality itself has a troubled history. Often mishandled in vulgar Marxist practice, typicality can take the form of “reducing characters to mere allegories of social forces” (193). However, typicality is to be understood not as a “matter of photographic accuracy” but instead as “an analogy between the entire plot, as a conflict of forces, and the total moment of history itself considered s a process” (194-95). In part as a result of the interesting contradictions inherent in the term “type” itself, there exists, therefore, always a doubled notion of typicality in Lukács: the typicality that produces rich, living characters who develop in relation to the dynamism of history; and its emptied-out counterpart, the typicality that produces the opposite of such characters, namely static types that resemble stereotypes or archetypes. It is this negative definition of typicality, the static opposite of the form of typicality Lukács advocates, I discuss in this passage, since it is precisely such historical and developmental evacuation on the level of literary characters with which authors such as Robinson are concerned. It should be noted here, that a more precise distinction would include a detailed discussion of a wider terminological framework Lukács himself offers, which would distinguish between dialectical types and static typicalization Lukács describes in his discussion of the novels of Willi Bredelas “Chargen,” a term borrowed from theatrical language loosely translating from its usage in a German context to “stereotypes.” See Essays on Realism (Cambridge: MIT, 1981) 24-27.

Examples include the work of Chuck Palahniuk, Bret Easton Ellis, Jonathan Safran Foer, Richard Russo, Annie Proulx, and Karen Tei Yamashita.

Jameson, Marxism and Form xiv.

Jameson, Marxism and Form 10.